By: Natalia Diamond, reviewed by James Richardson, registered dietitian and sports nutritionist

Before we bust various common nutrition myths for swimmers, we feel a preamble is necessary.

Diving into the world of swimming demands dedication, long hours and many very early mornings. It’s also undeniable that proper fuelling is crucial for swimmers. Despite this fact, many swimmers fail to meet and prioritize their dietary needs.

A recent study involving female collegiate swimmers found that 95.9% fell short of meeting the recommended dietary allowances (RDA) for carbohydrates, protein and fat. It is important to highlight that the RDA is just the baseline health requirement. It doesn’t even consider the additional energy and nutritional needs of athletes like swimmers. Having inadequate nutrition for an athlete not only negatively impacts performance in terms of fatigue, recovery, and maximal capacity but also increases the risk of illness and injury.

In the world of competitive swimming, where every stroke and turn counts, proper nutrition is not just important, it’s crucial for peak performance and optimal recovery. Yet, despite its significance, many still fall victim to common nutrition myths for swimmers.

Therefore, in this post, we’ll dive deep into the pool of misinformation and bust 10 prevalent myths that may be hindering your swimming performance.

Let’s jump in and uncover the truth.

Nutrition Myths for Swimmers:

Myth 1: Exercising on an empty stomach is superior and skipping pre-workout meals is fine

This is a relatively common nutrition myth for swimmers.

Fuelling up before a workout is crucial, not only for peak performance during practice but also for optimal recovery afterward. It’s recommended to have a pre-workout meal 3-4 hours prior to your training session, along with smaller, easily digestible snacks 1-2 hours before.

When planning your pre-workout meal, consider these three key factors:

1. Prioritize Carbohydrates

Making sure you have a sufficient amount of carbohydrates before your workout ensures your energy stores are fully stocked in your muscles and liver. This enables you to push yourself to the max, especially during high-intensity exercises.

Aim to consume 1-4 grams of carbohydrates per kilogram of your body weight in your pre-workout meal.

What would this look like?

For a 70 kg athlete (154 lbs.), this would translate to approximately 70-140 grams of carbohydrates.

Example: 2 slices of whole wheat bread with peanut butter provide around 60 grams of carbohydrates, while 1 cup of oatmeal with fruits adds another 60 grams.

2. Include Protein

Research has shown that consuming protein before exercise can boost muscle protein synthesis and prevent muscle breakdown compared to having a pre-exercise meal lacking in protein. Aim for 20-25 grams of high-quality protein.

3. Limit Fibre and Fat Intake

Meals that are high in fat and fibre can lead to bloating, gas and an upset stomach, which is far from ideal before or during a training session.

However, it’s important to note that tolerance levels vary among athletes based on their usual dietary intake. Some athletes may handle these nutrients better and should adjust accordingly.

Tip: Because it’s not always possible for many athletes to get a full meal in 2-4 hours before training, be sure to have a pre-workout snack (simple carbohydrates with some protein).

Myth 2: All athletes require the same amount of carbohydrates

This is another prevalent nutrition myth for swimmers.

Carbohydrates play a fundamental role in an athlete’s diet, serving as the primary source of energy for both muscles and the brain. It’s no secret that low carbohydrate intake can lead to adverse effects for athletes. This includes fatigue, reduced concentration, impaired training adaptation and an increased risk of injury.

One common misconception is that carbohydrate needs are uniform across all athletes or remain static within each individual.

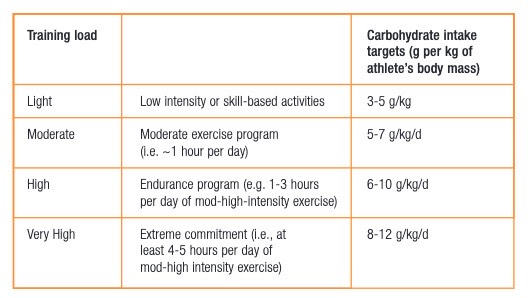

Carbohydrate intake, however, should fluctuate based on the energy demands of training. Put simply, as training intensity increases, so should carbohydrate consumption.

Additionally, it’s crucial to understand that carbohydrate needs are highly personalized. They are influenced by factors such as gender, training volume and intensity, energy expenditure, type of exercise and environmental conditions.

While research suggests that athletes should aim for consuming 6-10 grams of carbohydrates per kilogram of body weight on average, it’s essential for athletes to fine-tune their carbohydrate intake to suit their unique circumstances and optimize performance.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) outlines carbohydrate intake defined by training load:

- Chart courtesy of The International Olympic Committee (IOC)

Myth 3: Protein serves as a fuel source for working muscles

No nutrition myths for swimmers list would be complete without this one.

Protein holds a vital place in an athlete’s diet, but not as a primary fuel source. Its main function lies in being the essential building block for our bodies, aiding in the repair and synthesis of tissues, such as muscles.

If you have an adequate intake of carbohydrates, your body will use the majority of your protein intake towards building and repairing tissue (protein-sparing effect).

If you are following a low-carb diet, however, your body is far more likely to use those proteins for energy. This is less optimal for athletes.

Myth 4: Athletes require extremely high levels of protein

This is another swimmer’s nutrition myth.

A prevalent misconception regarding protein intake is the belief that athletes need it excessively high amounts.

While sufficient protein intake is crucial, the efficiency of protein utilization actually increases with high training volumes.

Trained individuals, like swimmers, can derive greater benefits from the same amount of protein. There is no evidence supporting the notion of increased protein requirements for athletes as long as they meet their energy needs. Any excess protein is simply excreted, rather than utilized.

So, how much protein do you actually need?

Studies suggest that athletes should aim to consume approximately 20-40 grams of high-quality protein per meal. This is equivalent to 0.25-0.4 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight ( or 1.5-2g/kg BW per day).

These meals should be spaced out every 3-4 hours throughout the day to maximize your muscle protein synthesis rates.

In terms of your post-workout meals, athletes should aim to consume a post-exercise meal containing at least 20-25 grams of high-quality protein within an hour after their workout, alongside carbohydrates.

Studies indicate that post-workout meals containing both carbohydrates and protein offer the most optimal effects on energy storage and muscle recovery compared to meals with solely protein or carbohydrates.

Myth 5: Carb-loading before a race is an outdated and ineffective technique

One of the more common nutrition myths for swimmers pertains to carb–loading.

Making sure you’re properly fuelled before a competition is paramount in sports performance.

While some may view carb-loading as an antiquated method, it remains an effective technique for gearing up before a competition.

Carb-loading involves super compensating glycogen stores, ensuring ample fuel to perform at peak levels during the event. Glycogen stores are just a fancy way of saying your body’s energy stores.

When you consume more energy (in the form of carbohydrates) than your body needs immediately, it stores this excess energy in your muscles and liver for later use.

Unquestionably, optimizing glycogen stores before a competition is crucial to avoid relying solely on carbohydrates during the event, which can lead to performance declines and fatigue.

What’s more, carb-loading is particularly beneficial for athletes engaged in events lasting longer than 90 minutes.

For effective carb-loading, aim for a carbohydrate intake of 9-12 grams per kilogram of body weight per day in the 24-48 hours leading up to the event.

Myth 6: Skipping breakfast before morning practice is okay

This has to be one of the more prevalent nutrition myths for swimmers. No doubt.

Early morning workouts are a hallmark of swimming. That said, many swimmers find themselves skipping breakfast due to lack of appetite at such an early hour.

This habit, however, might be counterproductive, leading to early fatigue and compromised recovery.

Research indicates that consuming as little as 30 grams of easily digestible carbohydrates before a morning training session can significantly enhance performance. This could be as simple as eating a single banana, which contains approximately 31 grams of carbohydrates.

Consequently, fuelling up even with a small snack before morning practice can make a big difference in your performance.

Tip: Make sure to have a more full well-rounded breakfast or meal following the practice, once your appetite returns.facilitating the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K).

Myth 7: Fat is bad, and a low-fat diet is ideal for athletes

This is not only a common nutrition myth for swimmers, but also a common nutrition myth, period.

Despite the negative portrayal of fat in the media, it’s actually a crucial component of a healthy diet, especially for young, active athletes.

Fatty acids serve as the primary energy source for low to moderate intensity and prolonged exercises.

Beyond energy provision, fats play vital roles in regulating hormones, maintaining nerve function, controlling body temperature, supporting immune function and facilitating the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K).

According to the Dietitians of Canada Nutrition and Athletic Performance guidelines, approximately 20-25% of an athlete’s total energy intake should come from various sources of fats, including both animal and plant-based options.

Within this intake, prioritizing healthy fats such as mono- and polyunsaturated fats is recommended.

Additionally, incorporating sources rich in omega-3 fatty acids, including EPA, DHA, and ALA, is beneficial. Some evidence even suggests that EPA and DHA may reduce muscle soreness and enhance endurance capacity.

To this end, rather than hating on fats, athletes should focus on including a diverse range of healthy fats in their diets to support optimal performance and overall health.

Myth 8: Since I’m in the water, I don’t sweat

Let’s take a closer look at this nutrition myth for swimmers.

While it’s true that swimmers may not sweat as visibly as athletes who take part in other sports, they still lose a significant amount of fluid through sweating. This is especially true in warmer water temperatures.

Without a doubt, continuous hydration is crucial for maintaining performance and supporting recovery.

Ensuring proper hydration before and during practice is essential for swimmers.

While the traditional approach is to drink when thirsty, relying solely on thirst may not be sufficient for athletes.

Related: The importance of drinking water

New recommendations suggest that athletes develop a personalized fluid plan to ensure adequate hydration. A general guideline is to drink at a rate that replaces the fluid lost through sweat during exercise.

After exercise, it’s important to focus on replenishing lost fluids. This typically involves consuming 1.2-1.5 litres of fluid for every kilogram of weight lost during exercise.

Additionally, replenishing electrolytes lost through sweating, such as sodium and potassium, is needed as well. By prioritizing hydration before, during, and after training sessions, swimmers can optimize their performance and recovery.

Myth 9: I don’t need to eat during a workout since I eat before and after

Although this is a less common swimmer’s nutrition myth, it’s one that warrants a deeper dive.

Contrary to popular belief, research suggests otherwise.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that consuming fuel during training can significantly enhance performance. This includes benefits such as sustaining an optimal pace, spending more time at higher intensities and maintaining skills and concentration throughout the workout.

Related: How to Boost Energy

Recent recommendations highlight the importance of adjusting carbohydrate fuelling strategies based on the duration and intensity of the workout. It’s advised to refuel during exercises lasting longer than an hour. During this time, the focus should be on consuming easily digestible carbohydrates along with fluids. This can include options such as sports drinks, energy gels, gummies, and fruits such as dates, apricots, bananas and applesauce.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) provides general recommendations for carbohydrate intake during exercise:

- For sessions lasting 45 minutes to 75 minutes at sustained high intensity, small amounts of carbohydrates (e.g., mouth rinse) are recommended.

- For endurance activities lasting 1 to 2.5 hours, including intermittent stops and starts, 30-60 grams of carbohydrates per hour are advised.

- For ultra-endurance activities lasting over 2.5 hours, intake of up to 90 grams of carbohydrates per hour is recommended.

By incorporating fuelling strategies during workouts, athletes can optimize their performance and endurance levels.

Myth 10: I need to take supplements to perform well

Unquestionably, this is a nutrition myth for swimmers (and other athletes) that we feel we must address.

The use of supplements is a highly debated topic in the nutrition world. While it’s widely believed that athletes can meet their nutritional needs through a balanced and varied diet, we acknowledge that this may be more challenging for some individuals.

It’s crucial to recognize that every athlete’s nutritional requirements are unique, and they should carefully consider the risks and benefits of supplements before incorporating them into their regimen.

There is a vast array of supplements on the market, ranging from those aimed at preventing deficiencies to those promising to enhance energy, performance and recovery.

Potential drawbacks to supplements

While some supplements may offer benefits to athletes, others could potentially harm their health, performance, and even their reputation, especially if they result in an anti-doping rule violation.

Numerous studies have revealed that many supplement products do not contain the ingredients they claim are there. Some may even contain undisclosed substances that could be harmful or prohibited under anti-doping regulations.

Therefore, it’s essential for athletes to seek expert professional advice or assistance before starting any supplement regimen.

To aid athletes in making informed decisions about supplements, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) has developed a flowchart to guide them through the process. This tool can help athletes navigate the complex landscape of supplements and make choices that align with their health, performance and ethical considerations.

Nutrition Myths for Swimmers Final Words

There you have it, a list of the most common nutrition myths for swimmers. If you feel we missed an important myth or misconception, please feel free to let us know.

Conclusion

If you’re interested in engaging our nutritionist who works with endurance athletes such as swimmers, book a free consultation or contact us for an appointment, and we will gladly lend a hand.

Other Related and Popular Posts:

How to Build Muscle and Lose Fat

Social Media Nutrition Myths Debunked

Nutrition Myths for Endurance Athletes

Strength Training Diet Nutrition Myths

Pros ad Cons of AI in Dietetics

References

Areta, J. L., Burke, L. M., Ross, M. L., Camera, D. M., West, D. W. D., Broad, E. M., Jeacocke, N. A., Moore, D. R., Stellingwerff, T., Phillips, S. M., Hawley, J. A., & Coffey, V. G. (2013). Timing and distribution of protein ingestion during prolonged recovery from resistance exercise alters myofibrillar protein synthesis: Timing of protein ingestion after exercise. The Journal of Physiology, 591(9), 2319–2331. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2012.244897

Asche, A. [@eleatnutrition]. (2020, May 8). Pre-workout Nutrition [Instagram photo]. https://www.instagram.com/p/B_7f0XmA7nh/?igshid=YmMyMTA2M2Y=

Beck, K. L., von Hurst, P. R., O’Brien, W. J., & Badenhorst, C. E. (2021). Micronutrients and athletic performance: A review. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 158, 112618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2021.112618

Burke, L. M., Hawley, J. A., Wong, S. H. S., & Jeukendrup, A. E. (2011). Carbohydrates for training and competition. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29(sup1), S17–S27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2011.585473

Hassapidou, M. (2011). Carbohydrate requirements of elite athletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(2), e2–e2. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2010.081570.23

Holtzman, B., & Ackerman, K. E. (2021). Recommendations and Nutritional Considerations for Female Athletes: Health and Performance. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 51(Suppl 1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01508-8

Logue, D. M., Madigan, S. M., Melin, A., Delahunt, E., Heinen, M., Donnell, S.-J. M., & Corish, C. A. (2020). Low Energy Availability in Athletes 2020: An Updated Narrative Review of Prevalence, Risk, Within-Day Energy Balance, Knowledge, and Impact on Sports Performance. Nutrients, 12(3), 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030835

Maughan, R. J., & Burke, L. M. (2012). Nutrition for Athletes. 1–66.

Maughan, R. J., Burke, L. M., Dvorak, J., Larson-Meyer, D. E., Peeling, P., Phillips, S. M., Rawson, E. S., Walsh, N. P., Garthe, I., Geyer, H., Meeusen, R., van Loon, L., Shirreffs, S. M., Spriet, L. L., Stuart, M., Vernec, A., Currell, K., Ali, V. M., Budgett, R. G. M., … Engebretsen, L. (2018). IOC Consensus Statement: Dietary Supplements and the High-Performance Athlete. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 28(2), 104–125. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0020

Maughan, R. J., & Shirreffs, S. M. (Eds.). (2013). Food, nutrition and sports performance III. Routledge.

Mountjoy, M., Sundgot-Borgen, J., Burke, L., Carter, S., Constantini, N., Lebrun, C., Meyer, N., Sherman, R., Steffen, K., Budgett, R., & Ljungqvist, A. (2014). The IOC consensus statement: Beyond the Female Athlete Triad—Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(7), 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-093502

Park, J. (2019). Using physical activity levels to estimate energy requirements of female athletes. Journal of Exercise Nutrition & Biochemistry, 23(4), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.20463/jenb.2019.0024

Thielecke, F., & Blannin, A. (2020). Omega-3 Fatty Acids for Sport Performance-Are They Equally Beneficial for Athletes and Amateurs? A Narrative Review. Nutrients, 12(12), 3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123712

Vogt, M., Puntschart, A., Howald, H., Mueller, B., Mannhart, C., Gfeller-Tuescher, L., Mullis, P., & Hoppeler, H. (2003). Effects of Dietary Fat on Muscle Substrates, Metabolism, and Performance in Athletes: Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 35(6), 952–960. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000069336.30649.BD

Our nutrition blog has been named one of the Top 100 Nutrition Blogs, Websites and Newsletters to Follow in 2021, 2022 & 2023 and one of the Top Canadian Nutrition Blogs by Feedspot. So don’t miss out and subscribe below to both the newsletter that includes latest blog posts.

JM Nutrition is a nutritional counselling service by registered dietitians and nutritionists in Canada. Main office: nutritionist Toronto.

For specific information on other areas of service, visit: dietitians servicing Ottawa, Halifax, Vancouver, Edmonton, Calgary, Saskatoon, Regina, Winnipeg and more.